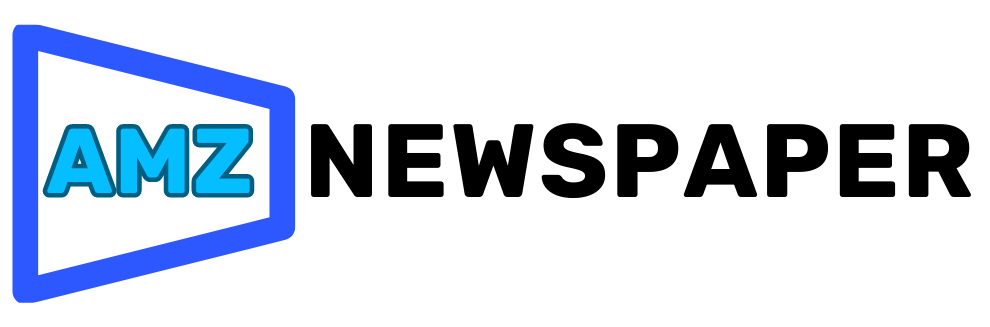

With its shattering performance and heavy armament, Messerschmitt’s Me 262 was a deadly opponent for any Allied aircraft, yet its impact was only felt during the last few months of the Second World War. Its development had begun in 1938, so what really happened?

Messerschmitt’s fearsome twin-engine Me 262 jet fighter began combat operations during the summer of 1944, but it was only during the winter and spring of the following year that it began shooting down Allied aircraft in alarming numbers. Many different explanations for this oddly late arrival on the front line have been offered over the past 77 years. Indeed, it has become almost obligatory for any author tackling the subject to simply pick their favourite and stick with it. The most commonly cited explanations include a crippling shortage of Jumo 004 engines, American bombers wrecking production lines or Hitler meddling in the aircraft’s development. Poorly trained pilots, a weak undercarriage and the general uselessness of both the Nazi government and the Luftwaffe have often been thrown into the mix too. Yet careful study of period German sources reveals a more complex and nuanced story.

The Messerschmitt company began preliminary studies of jet aircraft designs during the late summer of 1938 and was formally commissioned to start work on a jet fighter that October. A specification — for a single-engine design — was delivered by the German air ministry, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM), on 3 January 1939, and various layout concepts were examined before it was decided two engines would be needed owing to the weakness of early jet powerplants.

The project was designated P 1065 (also sometimes referred to as P 65) in April 1939 and a triangular fuselage cross-section was chosen in order to provide space for the mainwheels, their positioning otherwise being restricted by the wing-mounted engines. Straight wings had been planned, but when it transpired that the engines would be longer than originally forecast, the outer wing sections were swept back slightly to compensate and maintain the centre of gravity. A tailwheel arrangement was used but early on Willy Messerschmitt, who was personally overseeing the project, sketched out a design for the aircraft showing a nosewheel.

A preliminary project description was submitted to the ministry on 7 June 1939. Various different wing, fuselage and engine arrangements were studied, wind tunnel testing conducted and meetings held with BMW, whose P 3304 jet engine was intended for the P 1065 series production model. The first prototype, P 1065 V1, would receive the P 3302 — an engine type BMW had acquired when it bought Bramo. Work on detailed drawings for the P 1065 V1 commenced in November 1939 and an airframe mock-up was inspected and approved on 19 December.

In short, the P 1065 was making good progress. However, on 19 February, Willy Messerschmitt wrote to General-Ingenieur Gottfried Reidenbach at the RLM to warn that delays were expected: “We inform you that we are constantly co-ordinating our own dates with the delivery dates communicated to us by the engine supplier [BMW] via the Air Ministry. Since we were last given the date of delivery for the engine of 1 July 1940, based on our telephone inquiry […] on 16 February 1940, we will ensure that the airframe is ready by the time the engine is received.

“We have so far postponed the earlier dates that we had intended, as it is not necessary to finish the airframe before the engines arrive. This measure has made it possible for us to continuously incorporate corrections after receiving the results from the wind-tunnel testers. If you agree, we will continue to do this in the future.”

Messerschmitt’s policy of failing to complete airframes before the associated engines had been delivered would have unfortunate consequences for the Me 262 later. An order for three prototypes was placed on 1 March and a full project description complete with construction details was produced by Messerschmitt on 21 March. Three months later, the ministry issued a new schedule which included the production of 20 P 1065s. The first was expected in September 1940, followed by two more in October, three in November, five in December, five in January 1941 and four in February.

But, around this time, work on the P 1065 appears to have ground to a halt. Messerschmitt wrote to Reidenbach again on 26 September to explain, “Due to the stressful work given to our design office and our experimental team as a result of the war requirements, we have been forced to pull workers out of prototype programmes that are to be completed later and are not yet at the front. We will do this in the following order: the Me 210 is disturbed as little as possible. The P 65 follows. First and foremost, workers will only be removed from the Me 209.”

Yet despite Messerschmitt’s pledge to only remove workers from the ongoing Me 209 development programme, the evidence speaks for itself: the P 1065 had been put on hold. During this period — essentially the duration of the Battle of Britain — the company was putting much of its effort into developing the Bf 109 and Bf 110, while concentrating any remaining capacity on preparing the already-troubled Me 210 to succeed the latter.

Pressure on the project office evidently eased in November 1940, again in parallel with the period generally recognised as covering the Battle of Britain: 10 July-31 October 1940. But by now Willy Messerschmitt had evidently lost interest in the P 1065, and the company’s experimental and design resources were committed instead to the design of a long-range bomber based on the Me 261 long-range transport aircraft.

He wrote to the Luftwaffe’s chief engineer Generalstabsing Lucht on 29 November 1940 to say, “For me, the lack of designers is actually the only thing that prevents me from completing such tasks [the further development of a long-range reconnaissance/bomber design] quickly. The few designers that I have are almost all busy with carrying out the ongoing improvements, change instructions, etc, of the two models running in series [Bf 109 and Bf 110].”

Messerschmitt relayed more bad news to project office leader Woldemar Voigt in a memo on 10 January 1941: “Subject: Me 262. According to a message from BMW, Munich, dated 7.1.41, delivery of the engines is not expected any time soon. Reasonably reliable dates cannot be set. For this reason, the 262 should only be accelerated in construction to the extent that is important for testing of flight characteristics and performance.”

This represents the earliest known use of the RLM number 8-262 for the P 1065. The following day, Messerschmitt wrote to the company’s chief design engineer Richard Bauer: “All documents for [Me 262] V1, V2 and V3 should have been delivered to you. However, a number of variants are still to be expected for these three aircraft, as they are to be used exclusively for flight characteristics and later engine tests. I ask for the completion dates for the individual aircraft to be determined”. Plans to fit a prototype with a nosewheel were also laid at this time.

The 20 prototypes optimistically scheduled by the RLM six months earlier had been boiled down to just three — and none of them had been completed. Requirements placed on the company during the Battle of France and the ensuing Battle of Britain had dramatically delayed the programme of airframe development, while BMW had similarly failed to supply the powerplants essential for flight-testing.

Distractions

Slow progress continued throughout 1941, with BMW missing deadline after deadline for delivery of the Me 262 V1’s engines. The project office pursued designs for a pulse-jet-powered fighter which would become the Me 328 and had its work cut out in designing both the Me 264 long-distance bomber — 30 examples of which had been ordered — and the Me 309, the chosen replacement for the Bf 109.

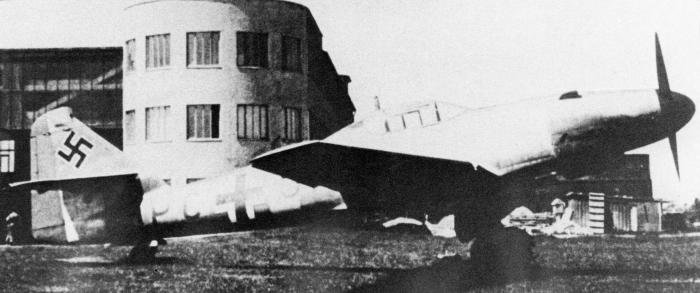

At 19.35hrs on 18 April, Flugkapitän Fritz Wendel took the Me 262 V1 up for its first flight, albeit powered only by a Jumo 210 G piston engine in its nose. This would be the first of more than 40 such tests without the use of jets, which continued into September 1941 when installation of two BMW P 3302s began.

Willy Messerschmitt’s interest in the Me 262 seems to have been abruptly reawakened on 14 August 1941, the day after the Me 163 prototype made its first powered flight. This latter event ought to have been a cause for celebration within the Messerschmitt company, but instead it seems to have deepened a growing divide between Prof Messerschmitt and Voigt on one side and Alexander Lippisch, head of Messerschmitt’s second project office, on the other.

Messerschmitt wrote a memo referring to a test flight report of 7 August: “The results of the experiment are incomprehensible, the values are considerably worse than the wind tunnel measurements with small nominal values. Has it been established whether the aircraft can even be pulled to the largest angle of attack? What further tests can be carried out to achieve the real maximum lift coefficients?

“The test flights were carried out between 18 June and 7 July, yet the test report was not made out until 7 August and it did not come to me until 13 August. I ask for suggestions as to which measures must be taken to prepare the test reports in a considerably shorter time. This processing period means an unnecessary loss of time and prevents the tests from being repeated in good time.”

Serious thought was now given to equipping the Me 262 with a Junkers jet engine, known as the T1, rather than relying on BMW. A production schedule drawn up on 7 October by Anselm Franz, who was leading the T1’s development, indicates that the ministry had now ordered enough T1s to power 20 Me 262s by August 1942 — a total of 60 engines, including 20 spares.

Meanwhile, the delivery schedule for the Me 210 heavy fighter had slipped and slipped again throughout 1941 as Messerschmitt’s engineers struggled to overcome the type’s tendency to ground-loop, its fire-prone DB 601 engines, its porpoising in level flight and unacceptable elevator buffeting with its dive brakes extended.

Desperate for the Me 210, the Luftwaffe put pressure on chief of procurement and supply Ernst Udet to get it fixed and put into service. Udet had done everything he could think of to make Messerschmitt aware of this urgency and to try and reach a solution, but to no avail. On 17 November 1941, Udet committed suicide and his position was filled by Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch — a man well known for his intense personal dislike of Willy Messerschmitt.

The Me 262 V1 first flew with P 3302 engines on 25 March 1942. During initial taxiing, Wendel found that both engines cut out when their throttles were moved back too far. Having restarted them, he needed 800-900m of runway to get airborne, taking off at 19.29. After climbing for 20 seconds, he levelled and the air speed rose to 400-450km/h. However, he then found he could not reduce the engines’ revs. Attempting to throttle back resulted in the failure of the port-side fuel injector and subsequent extremely rough running of that powerplant. After cutting it, Wendel accidentally cut the starboard engine too by backing it off too much. Despite a high rate of descent, he managed to land normally, albeit breaking the shock struts of the aircraft’s main landing gear. In his report, he concluded, “in its present condition the aircraft cannot be handled by an average pilot.”

This disappointing experience, however, was just a sideshow to what was happening elsewhere within the Messerschmitt company. Neither Willy Messerschmitt himself nor the ministry were focused on the Me 262. All eyes were instead on the unravelling Me 210 disaster.

During the RLM management meeting of 14 April 1942, it was decided that Messerschmitt should be removed from the leadership of his own company. Five days later, Göring cancelled the Me 210. The order would be rescinded less than a month later, but the damage had been done. The Messerschmitt firm was left in turmoil and on the brink of bankruptcy. And the Me 262’s development continued to languish at the bottom of a very long list of more urgent priorities.

Me 209 interference

Following Wendel’s disastrous flight, on 29 May the ministry decided to limit Me 262 prototype production to just five examples. The total order remained at 20 aircraft, but the other 15 would only be approved for construction following successful flight-testing of the first five.

At this point — two-and-a-half years after they were originally ordered — the Me 262 V2 and V3 were both close to completion, the latter with Jumo T1 turbojets installed. Confidence in the T1 must have been high since there was no suggestion that a nose-mounted piston engine would be needed this time, and the Me 262 V3 took to the air at Leipheim on 18 July 1942. Wendel made his first flight at 08.40, lasting 12 minutes, and a second at 12.05, of 13-minute duration.

On both occasions the engines reportedly performed satisfactorily but there was no joyous celebration. As Messerschmitt vice-president and commercial director Rakan Kokothaki recalled shortly after the war, “The big event of the first flight of the Me 262 with two Junkers 004 jet units on 17 July 1942 went by completely unobserved. Because of the general agitation incited anew against Messerschmitt [owing to the Me 210 debacle], no official recognition was given to this very important event.”

Development continued throughout the remainder of 1942, and by December the first three Me 262 prototypes had flown fewer than 50 times between them, with only 15 of those flights being made under jet propulsion. Much greater attention had been lavished on the Me 309, but now this too was in trouble. Flight-testing had revealed poor climbing performance compared to the Bf 109.

The Luftwaffe essentially rejected the Me 309, and in its place Willy Messerschmitt hastily offered a 109 airframe modified to accept the 309’s DB 603 engine. This had been designated Me 209 by 2 February 1943, though it had very little in common with the original 209 of the late 1930s, being mostly composed of standard Bf 109 G parts. At the RLM, plans were now being drawn up to mass-produce the Me 262, but the Messerschmitt company had no such intentions. Indeed, it seldom had more than one airworthy prototype available for testing at any one time.

During a ministry meeting on 19 March, officials noted how Junkers now had T1 prototypes sitting around that it was unable to test due to a lack of airframes. Messerschmitt’s policy of only completing aircraft when engines had physically been delivered meant the number of airframes available was now woefully inadequate and was causing a bottleneck in development.

At another ministry meeting on 31 March 1943, it was suggested the Me 209 should be cancelled and all resources put into building the Me 262 instead. The Luftwaffe’s general of fighters, Adolf Galland, was sceptical but Milch appears to have been intrigued by the notion. Galland travelled to Lechfeld on 22 May and flew the Me 262 V4 himself — his experience, famously, being overwhelmingly positive. Three days later, it was decided the Bf 109 should be phased out and the Me 209 cancelled in favour of the Me 262, with Focke-Wulf Fw 190 production being increased to cover the shortfall in fighters during the switchover.

Recognising this growing interest in the Me 262, Willy Messerschmitt had his staff commence a near-complete redesign of the aircraft. It was to incorporate a nosewheel as standard, the cockpit layout, canopy and weapons bay were to change, and wiring patterns were established which would allow bomb racks to be installed.

All of this meant the Me 262 was nowhere near ready for production. Horrified by the idea that his Bf 109 production lines — which he had thought to simply upgrade to producing the Me 209 — would be closed and repurposed to the Me 262, Messerschmitt initially had no choice but to go along with it.

Then, on 27 June 1943, without Göring’s knowledge, Adolf Hitler summoned seven key figures in the German aviation industry to attend his Berghof residence on the Obersalzberg, near Berchtesgaden. These were Ernst Heinkel, Claude Dornier, Focke-Wulf’s Kurt Tank, Arado’s Walter Blume, Richard Vogt from Blohm & Voss, Heinrich Hertel from Junkers and Willy Messerschmitt.

The Führer spoke to each individually behind closed doors, offering them an opportunity to air any grievances they might have. It is unknown exactly what Messerschmitt said but exactly a month later, on 27 July, Milch’s staff were surprised to learn the Me 209 was suddenly back on the schedule and the Me 262 had been relegated to an “additional requirement”. It appears Hitler had intervened on Messerschmitt’s behalf to completely undermine the plans laid by both the ministry and the Luftwaffe. Messerschmitt himself was at the 27 July meeting and commented, “You can’t just go straight to the jet fighter.”

Hitler’s fighter-bomber

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring explained to a meeting of RLM officials on 28 October 1943 that Hitler was concerned about the possibility of an invasion from Britain and had “said that the decisive factor is the jet fighter with bombs, because at the given moment they can whiz along the beach and throw their bombs into the mass that has been formed there.”

Göring personally quizzed Willy Messerschmitt about the Me 262’s bomb-carrying capabilities during a meeting on 2 November and passed along Hitler’s command that the Me 262 should be a fighter-bomber. He received reassurances that this could and would be done. With Hitler on board, the tables were finally turned on the Me 209 and it was cancelled for good on 30 November, five months after it had displaced the Me 262 on the production schedule. Even so, the Bf 109 remained in full-scale production, as did the Me 210’s successor, the Me 410, and it was clear that only limited resources would be available for the Me 262.

To make matters worse, the German Army’s arbitrary conscription programme, known as SE Action, was becoming a real problem for the aviation industry. Targets were set and personnel were removed — even those working on ‘protected’ programmes. They then had to be claimed back, assuming it could be proven that they were working on a programme being run under the highest ministry priority. An RLM meeting on 1 December 1943 heard Messerschmitt had protection for 1,400 Me 262 workers and Junkers for 1,000 Jumo 004 workers under the third round of conscription, but Junkers still had to give up 900 other personnel. Overall, the aviation industry had to meet a quota of 15,000 men for the army with more conscription still to follow.

Conversely, Allied bombing had minimal direct impact on Me 262 production. The American ‘Big Week’ raid against Messerschmitt’s Augsburg factory on 25 February 1944 severely damaged some storage sheds but left production lines, jig and machine tool manufacturing intact. The RAF made a bigger impact the following night by hitting Augsburg itself and destroying workers’ homes. It was estimated that in the following two weeks the absentee rate at Messerschmitt rose to about 50 per cent, during which time workers were attempting to re-establish themselves.

Jägerstab

While struggling to set up Me 262 production lines, the RLM slowly came to realise that most of Germany’s top production specialists, including jig and tool-makers, had been surreptitiously bled away from the aviation industry by Albert Speer’s Ministry of War Production for work on the tank and small arms projects personally favoured by Hitler. As a result, Milch managed to negotiate the establishment of a joint Air Ministry/Ministry of War Production task force known as the Jägerstab. This would co-ordinate resources across all projects to ensure every essential programme got the resources it needed.

One of its first acts, on 1 March 1944, was to appoint its own production overseer at Messerschmitt’s Augsburg factory — Prof Hans Overlach, director of the Technische Hochschule Karlsruhe — much to the disgust of the company’s management.

Describing what happened for the benefit of American technical intelligence officers immediately after the war, Kokothaki wrote, “In the beginning of March, the aircraft production programme was taken over by the Speer ministry. Therefore, on 1 March 1944, a commissioner Gauamtsleiter Prof Overlach was attached to the Augsburg factory. From this time on, the factory’s [original] management was practically put out of action because direct orders were issued by this new office.”

The precise accuracy of this statement — whether Messerschmitt’s senior managers really were no longer able to control production at Augsburg themselves — is difficult to determine, but it certainly seems clear that Overlach’s appointment to this role was extremely unwelcome as far as the company was concerned.

The following day another meeting was held to provide a status update on all the various ongoing projects and developments associated with the Me 262. It was noted that bomb rack fittings would be installed “for the series from the sixth machine”.

The Führer’s fury

Göring began a three-day meeting in the Führer’s dining room at the SS Barracks Obersalzberg at 11.00 on Tuesday 23 May 1944. At some point during the day, with Hitler himself in attendance, the discussion turned to the Me 262 and Edgar Petersen, the Me 262 commissioner who was also in overall charge of the Luftwaffe’s test centres, evidently gave reassurances that the aircraft would soon be available as a fighter-bomber.

During the second day, however, the head of the RLM’s technical office, Siegfried Knemeyer, stated that the Me 262 would not be able to carry bombs due to centre of gravity issues. Göring was quick to grasp what this meant — everyone had spent the last six months under the impression that the Me 262 would be a fighter-bomber, when in fact it would not. Worse, it meant Petersen had lied to Hitler the day before. Further confusion reigned over whether the first 100 examples would have bomb rack wiring or not.

Willy Messerschmitt was summoned to appear at the next day’s meeting and managed to reassure all concerned that Knemeyer was wrong, Petersen had in fact been correct and only the first six series production machines would be without bomb rack wiring, but the damage was already done. Hitler had got wind of the previous day’s discussion and was furious at what he saw as his orders being deliberately ignored. On 27 May 1944, he therefore ordered that the Me 262 could not be a fighter or a fighter-bomber. Instead, it would be put into service as a pure bomber and could only be used for bombing missions. This order would remain in place until November, with Me 262s rolling off the new production lines going straight to bomber unit KG 51.

Hitler eventually relented and allowed the aircraft to be used as a jet fighter following the intervention of Speer, who had Willy Messerschmitt write a document for the Führer explaining why the type should be used as a fighter. Summarising a series of meetings with Hitler from 1-4 November, Saur noted, “The Führer agrees that the Me 262 will now be released as a fighter in all its deployments, on the express understanding that each aircraft is capable of carrying at least one 250kg bomb if necessary.”

The Me 262, unquestionably Germany’s most powerful fighter, had been in service for seven months by the end of October 1944. And for nearly all of that time, despite the huge formations of Allied bombers regularly roaming across Germany to deliver one devastating raid after another, the Luftwaffe had been forced to use it as a bomber only.

Poor training

Even when the aircraft could be operated as a fighter, losses were appallingly high, around 50 per cent of them due to preventable errors by inexperienced and under-trained pilots. A report made by Messerschmitt personnel who had visited front-line Me 262 unit Kommando Nowotny from 7-8 November found that out of 30 Me 262s delivered since the end of October, there had been 26 losses. Of those, eight were in combat or as a result of combat damage, seven had crashed while attempting a normal take-off or landing, six after running out of fuel, three during a single-engine flight and one after its engines both stopped at 9,000m (29,527ft).

Potential unfulfilled

Willy Messerschmitt could hardly be blamed for failing to construct 20 P 1065 prototypes back in 1940, only for them to sit around engineless while BMW struggled to build even a single pair of reliable engines. His shift of focus towards long-range bombers and pulse-jets in 1941 is also understandable. The Me 210 debacle and its fall-out, however, caused both Messerschmitt himself and the RLM to overlook the Me 262’s potential when fitted with Jumo engines during 1942. Messerschmitt himself, wounded by the failure of the Me 210 and Me 309, threatened with the loss of the Bf 109, and realising too little had been done to develop the Me 262 for far too long, then deliberately sabotaged the jet fighter’s entry into full-scale production during 1943.

By the time the Me 262’s abilities finally were recognised, the RLM was too lacking in resources to get it and its engines built in the quantities required. The icing on the cake was the disastrous May meeting which convinced Hitler to order the type’s entry into service as a pure bomber only. And when the aircraft was finally approved for fighter operations, poor aircrew training severely reduced its effectiveness.

Had the Luftwaffe not taken a beating during the Battle of Britain, had the Me 210 not failed so spectacularly, had Hitler not acted on Messerschmitt’s pleas to save the Bf 109/Me 209, had the whole production process been staged just a little earlier in the war, and had Hitler not intervened again to prevent the Me 262’s use as a fighter, the type’s story might have been very different. As it was — perhaps fortunately for Allied aircrews — the Me 262 had resoundingly failed to achieve its full potential by the end of the war.

NOSE JOB

When Hitler ordered that the Me 262 should be a pure bomber, no example of the type had ever dropped a bomb. In fact, the Me 262 was spectacularly ill-suited to the bomber role. Downward visibility from the cockpit was poor, fitting an effective bomb-sight was a real challenge and bomb-carrying capacity was extremely limited. Consequently, the RLM, the Luftwaffe and Messerschmitt set to work on modifications that could turn the base aircraft into a bomber with the minimum of changes. Attention initially focused on a conversion of the B-1 two-seat trainer, with the back-seater operating a periscopic bombsight. However, it was determined that a 2m-long periscope would be needed to provide visibility past the bombs dangling beneath the aircraft’s nose. And the process of designing both the periscope itself and the modified cockpit would take at least nine months.

The ingenious alternative was to simply swap the aircraft’s cannon nose for a small, glazed cabin in which the bombardier could lie prone on his chest and operate a bombsight positioned in front of the bombs. This was to be the A-3 variant and might eventually have become the most-produced Me 262 sub-type. However, the new nose proved difficult to build out of wood — the only material available by late 1944 — and its fate was sealed by a failed stress test, where the wooden cabin splintered too easily. As such, the modification was confined to two flying prototypes and relegated to the A-2a/U2 designation.

THE TANK-KILLER

Messerschmitt set out plans to fit the Me 262 with a 50mm cannon as early as August 1943, though it was originally conceived as a tank-busting variant. Design work was carried out at a low level of priority, however, and shelved altogether when it was decided that the Me 262 would only enter service as a bomber. When Hitler finally changed his mind in November 1944 and allowed it to become a fighter, he quickly became enthused by the idea of attacking Allied bombers with weapons of the highest possible calibre.

The long-forgotten plan to install a 50mm cannon was dusted off in January 1945 and two prototype Me 262s were fitted with a single Mauser MK 214 cannon each. This created a highly effective bomber-killer, when the cannon could be persuaded to actually work. However, flight-testing could not commence until mid-March — far too late for the variant to enter series production, let alone front-line service.